Various: Disco Discharge: Pink Pounders, Digging Deeper, European Connection, Disco Boogie

An outstanding compilation series shows why disco overcame the haters and seeped into pop's DNA, writes Alexis Petridis

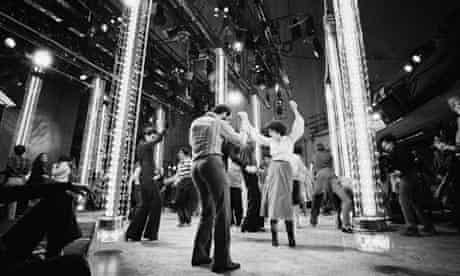

Disco Mecca … Studio 54. Photograph: Michael Norcia/Sygma/Corbis

Of all the bewildering moments in pop history, few are quite as bewildering as Disco Demolition Night. This was an incident that occurred in Chicago in 1979, when a local radio DJ called Steve Dahl invited listeners to bring disco records to a Chicago White Sox baseball game, where he would blow them up. About 90,000 people turned up. They threw beer and firecrackers, and stormed on to the pitch chanting "disco sucks!", starting fires and rioting. Thirty-nine arrests were made.

It's not the Disco Demolition's motivation that's baffling, although British onlookers might be a little startled at the amount of influence a local DJ could wield: if Dr Fox announced a fatwah on dubstep, he'd have difficulty enlisting enough people to fill a lift, let alone a stadium. It's more what happened in its aftermath: American record buyers didn't roundly condemn the stunt as the work of violent, hooting morons, laden with dark intimations of homophobia and racism. Instead, American record buyers acted as if they had a point. Within two months of the riot, the US top 10 had been cleansed of disco. "People were now even afraid to say the word," noted Chic's Nile Rodgers. Faced with a choice between, on the one hand, a load of cloth-eared thickos setting fire to things and smashing stuff up because some people had the temerity to like music they didn't, and, on the other, the people on the cover of Chic's C'est Chic – elegant, beautiful, insanely talented – the US record buying public acted as if the cloth-eared thickos were the cool ones, the disco musicians the embarrassment.

At the time, the notion that anyone would ever consider compiling a series of beautifully packaged, expertly curated disco compilations would have seemed weird and laughable, like Cahiers du Cinema publishing a scholarly essay on the oeuvre of Robin Askwith. Today, disco is enshrined in the general public imagination as an affected archaism, something tipsy hen parties dance to in comedy afro wigs, but what's striking about the content of these four double-CD sets – which follow last summer's first instalments in the series – is how current most of it sounds. Admittedly, there are things here that seem charmingly of their time. Voyage's glorious From East to West speaks of an age when air travel was still associated with rarefied glamour, rather than global warming and the Ryanair in-flight menu, while you probably couldn't get away any longer with the game attempt by Sticky Fingers, on the song Party Song, to blend Grieg's In the Hall of the Mountain King with the deathless "oooha! oooha!" whoop of the Michael Zager Band's Let's All Chant. But those moments are vastly outweighed by tracks that could conceivably have been released last week: the odd conjunction of sweet pop tune and disorientating electronics on Sylvia Love's Instant Dub, the exquisitely dead-eyed ode to loveless sex that is Poussez!'s Never Say Goodbye. That's partly because dance music is currently in the midst of one of its periodic disco revivals, but it's mostly because the Disco Demolition came too late: by the time the dickheads stormed the pitch, disco had already seeped into pop music's very DNA. People were bound to be endlessly inspired by disco, because the best of it pulled off the greatest trick of all: somehow managing to be both perfect, gleaming pop songs and endlessly adventurous experiments at the same time.

With most of the genre's unimpeachable classics already rounded up on the series' first four volumes, it falls to these eight CDs to unearth lesser-known gems, including of all things, a disco track by Toto, the soft rockers who later in their career blessed the rains down in Africa. If there's nothing on Pink Pounders with quite the jaw-dropping impact of the Boys Town Gang's Cruisin' the Streets (in fairness, given that its 13 minutes culminate with a playlet in which police officers punish a couple of cottagers by forcing them at gunpoint to take part in a orgy with a passing prostitute, there's not really much in musical history that has quite the jaw-dropping impact of Cruisin' the Streets), there are still things that leave you boggling at their abundant oddness, not least the Immortals' The Ultimate Warlord, which sets a distorted vocal against Hammer Horror organ and relentless four-to-the-floor beats.

Most remarkable of all might be USA-European Connection's There's a Way Into My Heart, a 1978 track that wouldn't seem out of place on a 2010 album by the critically acclaimed producer Lindstrom. It threads a euphoric chorus – underpinned with the weird, ineffable melancholy that seemed to lurk at disco's heart – through 12 minutes of astonishing musical shifts: swooning, melodramatic strings, Spanish guitar filigree, stark passages of hypnotic, repetitious riffing, a Pink Floyd-ish solo. You could argue the only thing that's missing is a lengthy improvisation on the kitchen sink, but equally, it's hard not to be stunned that anything this imaginative could ever be the subject of opprobrium: proof the past can still seem a foreign country, even when it sounds like the present.

Of all the bewildering moments in pop history, few are quite as bewildering as Disco Demolition Night. This was an incident that occurred in Chicago in 1979, when a local radio DJ called Steve Dahl invited listeners to bring disco records to a Chicago White Sox baseball game, where he would blow them up. About 90,000 people turned up. They threw beer and firecrackers, and stormed on to the pitch chanting "disco sucks!", starting fires and rioting. Thirty-nine arrests were made.

It's not the Disco Demolition's motivation that's baffling, although British onlookers might be a little startled at the amount of influence a local DJ could wield: if Dr Fox announced a fatwah on dubstep, he'd have difficulty enlisting enough people to fill a lift, let alone a stadium. It's more what happened in its aftermath: American record buyers didn't roundly condemn the stunt as the work of violent, hooting morons, laden with dark intimations of homophobia and racism. Instead, American record buyers acted as if they had a point. Within two months of the riot, the US top 10 had been cleansed of disco. "People were now even afraid to say the word," noted Chic's Nile Rodgers. Faced with a choice between, on the one hand, a load of cloth-eared thickos setting fire to things and smashing stuff up because some people had the temerity to like music they didn't, and, on the other, the people on the cover of Chic's C'est Chic – elegant, beautiful, insanely talented – the US record buying public acted as if the cloth-eared thickos were the cool ones, the disco musicians the embarrassment.

At the time, the notion that anyone would ever consider compiling a series of beautifully packaged, expertly curated disco compilations would have seemed weird and laughable, like Cahiers du Cinema publishing a scholarly essay on the oeuvre of Robin Askwith. Today, disco is enshrined in the general public imagination as an affected archaism, something tipsy hen parties dance to in comedy afro wigs, but what's striking about the content of these four double-CD sets – which follow last summer's first instalments in the series – is how current most of it sounds. Admittedly, there are things here that seem charmingly of their time. Voyage's glorious From East to West speaks of an age when air travel was still associated with rarefied glamour, rather than global warming and the Ryanair in-flight menu, while you probably couldn't get away any longer with the game attempt by Sticky Fingers, on the song Party Song, to blend Grieg's In the Hall of the Mountain King with the deathless "oooha! oooha!" whoop of the Michael Zager Band's Let's All Chant. But those moments are vastly outweighed by tracks that could conceivably have been released last week: the odd conjunction of sweet pop tune and disorientating electronics on Sylvia Love's Instant Dub, the exquisitely dead-eyed ode to loveless sex that is Poussez!'s Never Say Goodbye. That's partly because dance music is currently in the midst of one of its periodic disco revivals, but it's mostly because the Disco Demolition came too late: by the time the dickheads stormed the pitch, disco had already seeped into pop music's very DNA. People were bound to be endlessly inspired by disco, because the best of it pulled off the greatest trick of all: somehow managing to be both perfect, gleaming pop songs and endlessly adventurous experiments at the same time.

With most of the genre's unimpeachable classics already rounded up on the series' first four volumes, it falls to these eight CDs to unearth lesser-known gems, including of all things, a disco track by Toto, the soft rockers who later in their career blessed the rains down in Africa. If there's nothing on Pink Pounders with quite the jaw-dropping impact of the Boys Town Gang's Cruisin' the Streets (in fairness, given that its 13 minutes culminate with a playlet in which police officers punish a couple of cottagers by forcing them at gunpoint to take part in a orgy with a passing prostitute, there's not really much in musical history that has quite the jaw-dropping impact of Cruisin' the Streets), there are still things that leave you boggling at their abundant oddness, not least the Immortals' The Ultimate Warlord, which sets a distorted vocal against Hammer Horror organ and relentless four-to-the-floor beats.

Most remarkable of all might be USA-European Connection's There's a Way Into My Heart, a 1978 track that wouldn't seem out of place on a 2010 album by the critically acclaimed producer Lindstrom. It threads a euphoric chorus – underpinned with the weird, ineffable melancholy that seemed to lurk at disco's heart – through 12 minutes of astonishing musical shifts: swooning, melodramatic strings, Spanish guitar filigree, stark passages of hypnotic, repetitious riffing, a Pink Floyd-ish solo. You could argue the only thing that's missing is a lengthy improvisation on the kitchen sink, but equally, it's hard not to be stunned that anything this imaginative could ever be the subject of opprobrium: proof the past can still seem a foreign country, even when it sounds like the present.

Comments

Post a Comment